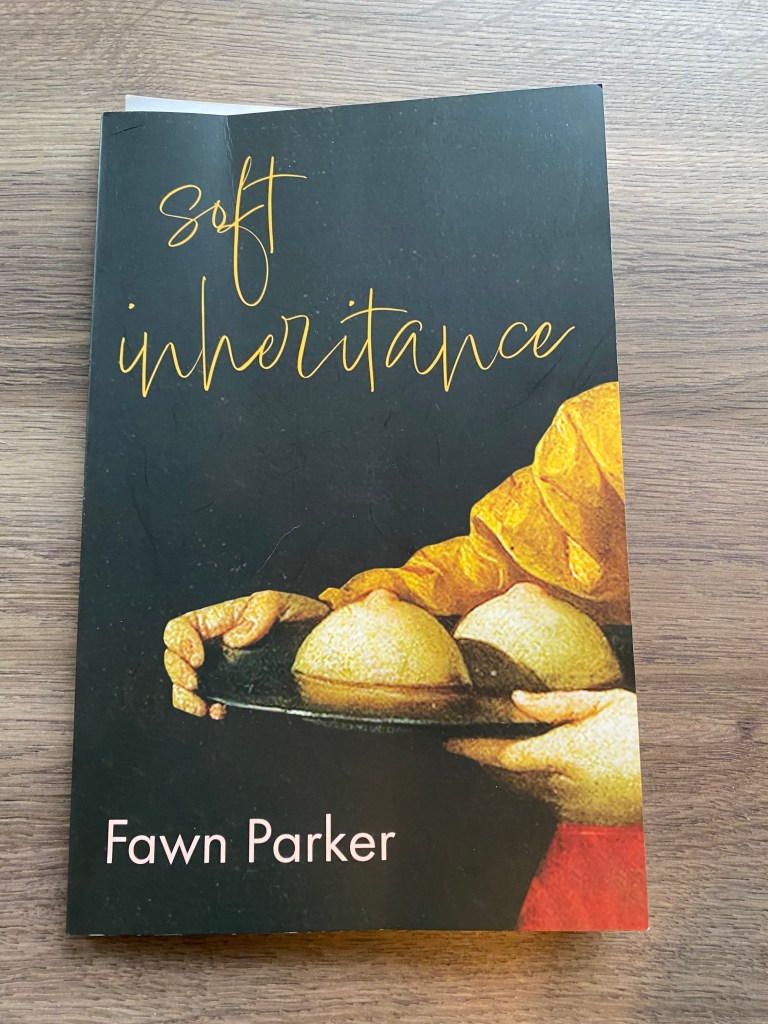

When I first read Fawn Parker’s Soft Inheritance, I was spellbound. I also felt slightly uneasy. Enthusiastically, I took notes. Then I read the book again. Once more, I was enthralled and discomforted, but this time I could say why, on a fairly basic level, at least — I was mesmerized by the beauty of the language in these poems, and I was deeply moved by the book’s tough and tender moments.

I sat with the book a while, reading snippets on my front step, trying to figure out its appeal. Because it did appeal. But it was also disquieting.

Then something came to me: Parker’s meditations on grief reminded me of C.S. Lewis’s in A Grief Observed — a book I’ve read a shameless number of times — in the sense that Parker’s poems often come across as difficult, eloquent confessions. Like letters from the land of grief. Letters written with raw honesty, uneasiness, and uncertainty. The uneasiness in these pages is electrifying and palpable.

For instance: “I am lonely and the thought / of others makes me sick,” the narrator of “Poem Against My Husband” admits, “at least in the mornings. / By night I’m in need again.”

Lewis wrote extensively about the loneliness of grief. (“There is a sort of invisible blanket between the world and me,” he wrote. “I find it hard to take in what anyone says. Or perhaps, want to take in.”) Parker touches on this too, in a similarly sincere and unapologetic tone. The feelings she expresses are instantly recognizable. Her honesty — her vulnerability — easily earn our trust.

Neatly, a bit playfully, the poem ends: “My work needs me like an infant — / this is why we understand each other.”

Parker wrote some of these poems when her mother was diagnosed with cancer. Others were written after her mother’s death. During that time, everything in Parker’s life was changing, bewildering, and painful, and these poems reflect that. When C.S. Lewis was shaken by the death of his wife, he wrote that he was surprised he could still work and write with ease. In her grief, Parker embraces a comparable conclusion: like an infant (a striking comparison, I think, given the context) needs tending to, so too does the narrator’s work. I love that these lines are open to multiple interpretations. That, I believe, takes skill and courage. It also acts as an exhilarating invitation to the reader. Is this what allows her to move forward? one might fairly ask.

The poem “Abracadabra” is just as dazzling and wise. “There were times you didn’t understand: / goodness is a scar,” it begins. Then comes a powerful middle stanza whose narrator is world-weary and distrustful, feels lost and unheard, and, in the end, unworthy: “We laugh until we twist / in horror and withdraw. / If you go to the party there will be someone there / who takes its out of you. / You want something from the party, / but the party is a beast / and you are speaking to some part of it / that isn’t its ear.”

The poem sadly concludes: “I am not a person deserving of a word / like light.”

Those last two lines linger hauntingly. Parker seems well aware that grief is, at times, a “beast” that can make you feel weak and worthless.

In the next poem, “Animal of Choice,” the speaker is in a sorrowful state where: “My friends are useless and it’s not their fault.” Also: “Things feel frivolous.” And the narrator can’t remember the “proper way” to pray. Grief does these things to people. Parker is sensitive to note them. She’s paying attention.

Throughout this collection, there’s a sense that Parker is trying to absorb and understand what’s happened to her and those around her. Life is cruel, hard and beautiful, she’s all but crying out, and not everything makes sense. The title poem “Soft Inheritance” encapsulates these feelings strikingly: “You’ve forgotten again: / kindness is a scar / though not all scar-makers are kind.”

These lines, as catchy as the lyrics of a very good pop song, stopped me in my tracks. Instead of trying to decode them, I let them shower over me. I liked the melodic rhythm of the verse; the words sounded lovely — and they felt quite true. To me, the sequence is so spectacular it feels important. And perhaps it is.

Not all scar-makers are kind.

You’d never guess this was Parker’s debut collection of poems.

In the poem “What Are We Here For,” she reflects on the guilt that often accompanies illness and grief: “Did I use up her / breath? / Repeating and repeating / her words to myself, / in my notebooks.”

The pause and a subtle line break here are perfect, powerfully evoking the strain of someone gasping for air. And the sentiment is stirring in its expression of guilt.

In the poem’s closing lines, Parker movingly captures the claustrophobia of illness and how it can make a home feel like something else: “The house is a hospital / a single room / an open cage / a staircase.” That a house can be both a hospital and an open cage is poetic and disorienting, as are many of the poems in this outstanding book.

Near the halfway point in Soft Inheritance, after Parker’s mother has died, she turns her attention to how we think and act when our loved ones are gone. In “Going Shopping,” after she comes across an entry in her mother’s journals that gives her pause, she laments: “Now that you are gone / I cannot learn from my mistakes, / be a good daughter. / Straighten the back, emote / in appropriate contexts. / Lately I don’t say a word.”

Parker’s mindful of the many sorrows that can shadow you in this state of “after” — the silent burdens we carry; how we try to please the dead.

The lines that follow are elegant and stirring: “At the funeral service / I read something old, / unaffected and academic / to everyone / you’ve ever known. / In this way I succeed / in being recognizable to you / should there be something / you-like in the air around the cemetery.”

Grief complicates our relationships. It also changes the way we see and think about our loved ones. Parker writes about these complications deftly in poems like “Ghost,” and “That Famous Night,” in which she reflects: “There are so many people / a person can be.” She begins looking at material objects differently, too — as “something more / than I’d had when I left / mourning already / that I’d have to leave it / behind.”

This strand of pre-mourning threads itself sympathetically through many of the poems in the final third of the book, including a poem that struck me as the most beautiful in the collection: “Their Shells Get Bleached By The Sun.” With exquisite imagery and rapturous language, the poem profoundly explores the complexities of grief. It left me gasping.

“I watch ladybugs crawl circles around the pane / the ones still red,” Parker writes, “and look only at the window, / never through / afraid of what I might see, / in place of what I want.”

Finally, in the poem’s closing lines, the ladybugs might be memories, or perhaps potential lovers: “They collect in the sills / and their shells are bleached by the sun. / I said I’d never kill them / but there are so many now that I do.”

If I were at a reading by Fawn Parker, my great hope would be that she would read this poem. That would be a sumptuous treat.

Near the end of the book comes “Goodbye to New York” — a fascinating take on how we grieve, and a good reminder that Fawn Parker is a talented novelist; the poem tells a good story. In it, she writes about how a man writes to her and says he mourns his wife only in fragments: “‘The issue is that this is the best you can do,’ / He said, describing his current work, / the work of grieving in smaller and smaller doses. / He said you don’t forget, you just / think more and more of other things, too.” And how true is it that? It’s interesting, too, I thought, that a man writes to explain this to her.

The book ends with another beguiling poem, “A Cover Over Everything.” This one is about relationships. Like a first snowfall, it’s gentle and dreamlike: “I’d rushed inside / to tell you that a bird fell out of the sky / and landed in the mouth of my shovel.” Momentum builds, charged by intimate details that feel like secrets, until the poem surges into a breathtaking ending — “I shed / the mess of bedding and went outside / in your sweater and boots, worked at the snow / until the bird fell. I figured the thing / was dead, or if not would somehow disappear / on its own. I couldn’t stand the thought / of trying and failing to save it.”

Loved ones who’ve died, people we love but only at a distance. Grief breaks us a little, in many ways, so that we eventually come to feel a fear so delicate it leaves us trepidatious if not helpless. Again and again, Soft Inheritance imparts this fragile feeling with astonishing sensitivity and power. Fawn Parker proves herself a skilled poet. Her first collection is a keen, generous, radiant work of art.

*****

Leave a comment