I have an addictive personality. I also love to read very good books. I like to collect them, too — various editions of favourite books, overlooked gems in the remainder bin, an armful of barely-read and well-loved cast-offs at a library book sale. If I go into a bookshop and leave without buying a book, I consider it a serious personal failure. I know it isn’t but it feels like it, and leaves me feeling muddled, if not a bit sad.

Years ago, a good friend came over to my apartment, a charming old second-floor one-bedroom walk-up on Quebec Street (which might sound like a nice street, but it was actually rather sketchy), with bathroom doors that could only be opened using a skeleton key, a peek-a-boo mail slot, and a rusty, wobbly fire escape off a kitchen window, which also occasionally served as a balcony. (Although I had to climb out the kitchen window to access it, and that was always precarious, especially if I had a beer in one hand.) At any rate, my place was filled floor-to-ceiling with CDs and books and movies, which that day prompted my friend, Brian, to say to me, “You know, you can only listen to one song at a time.”

I felt slightly hurt. How to defend myself? Eventually, I told him, “True, yeah. But I have lots to choose from. And I own them.”

“I just listen to the radio in my truck,” he said. “Bit of everything. And I can always flip the station.”

That sounded boring to me. Or more like the stuff of summer road trips. Anyway, he was missing the point, I thought.

“But this is like a library. My own library,” I said.

I think he shook his head. Maybe he mentioned money, and wasting it, like my dad often did. In any event, he wasn’t going to understand, so I gave up on the conversation and we talked about something else.

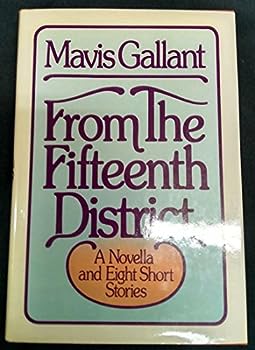

And just last winter, or perhaps the previous one, I was sitting in my parents’ garage reading a great book I’d just scored at a library used book sale: Mavis Gallant’s From The Fifteenth District. It was an older hardcover, in good shape, which I’d been thrilled to find a few days’s before. I’d been so happy with my haul; a tall stack of my other finds sat next to me atop Dad’s well-used, paint-speckled workbench.

“What are you gonna do with all those books?” my dad asked me.

I looked up. Sniffled a laugh. “Read ’em,” I said.

He made a face. “You don’t have enough books?”

“No,” I scoffed. “”Never!”

My next thought was kind of a sad one: I guess my dad will never understand me. Or that part of me, at any rate. He did recall I once opened my own bookshop, didn’t he? And that I’d had a novel published, and was hard at work on another?

Book lovers are often misunderstood. (So, too, are writers, but that’s likely another complicated story, best saved for another thread.) Book collectors are frequently misread as well.

My dear friend Steve — the late great (prodigiously brilliant and talented, really) writer and musician Steven Heighton — was over for a Music Night some years ago, and just back from the washroom, he said, “Johnny, you have this book in every room in your place.” He was holding an older trade paperback copy of Anne Morrow Lindbergh’s Gift From The Sea. Steve wasn’t teasing me or making fun of me, I don’t think. What he’d said merely sounded like an observation, one that seemed to amuse him.

“Yep, I do,” I said, doing the math in my head. There was a copy in the washroom, one on my nightstand, another in my main teak bookcase in the kitchen, and a fourth in the living room, on the TV stand. “I love it. It’s a favourite book. And whenever I see a used copy, I buy it. I like gifting it to people.”

Pretty sure he smiled at that, then sat back on his stool at my pub table, picked up his guitar, and we happily got back to the business of chatting and singing and laughing — well into the night.

I used to see people like me in my bookshop. The serious diggers. The first edition finders. The man who, one summer afternoon, paused before leaving the shop to say, “This is a wonderfully curated shop.” He didn’t buy anything, if I recall correctly, but he got it. He definitely got it. (And I am still, to this day, touched by his kindness.) A kindred spirit, that gentleman. There are others, I know. Many others. And I like these people.

This is all backstory, really, to what I’m feeling slightly uneasy about at the moment. The pickle is this: Can I read five books at once and write my novel — give it its due, and my all — at the same time?

But the answer comes easily: Yes, I can.

Some writers absolutely put blinders on when crafting a book. They won’t allow themselves to read other books. They’ll get away from home, retreat to a lakeside cottage, if possible — without a phone, or internet access, or another soul in sight. Anything that’s not in their notes or in front of them on the page is an unwanted nuisance. They require quiet. A clean sheet, a clear mind. And as few distractions as possible.

I get that. I’ve done similarly on writing retreats. Although I need my phone. And maybe two or three books for inspiration, a good notebook, and whatever books or magazines (though most often it’s books) I’m reading for research.

It might seem simple, but, to me, everything is research. Nora Ephron famously believed that “everything is copy.” Anything anyone around her said or did was up for grabs, and might just find its way into her work — it was fair game, all of it. I agree with that philosophy, although I dislike writing about the bad behaviour of people I know. Sometimes I don’t like writing about their good behaviour. Sharing those moments — as I have above, about my old friend, my dad, and Steve — is okay with me, I mean, of course it is, as long as it’s not done with malice or for showy reasons. We can share bits of our stories, and our memories, and that’s just fine with me because it’s very human (we are, indeed, a storytelling animal). If it does no harm, then, you know, work out. That’s my thinking, in essence.

I’ve wavered a bit, perhaps. My point is this: Reading a few pages at a time from one of the five books I’ve next to me on my coffee table is fine. It’s research. It’s inspiration. And when I take a break from writing, and sometimes simply want to unwind or try to blank out the screaming sirens on my busy street, I’ll allow myself to pick up Ann Patchett’s new novel, Tom Lake, and enjoy a few pages. I don’t need an excuse. It’s pleasurable. And yes, I very strongly believe reading is research.

Reading anything, really — a pamphlet at the pharmacy, a notice at the doctor’s office, a poster heavily stapled to a telephone pole. Observation is research. The mind is a sponge. Inspiration is everywhere.

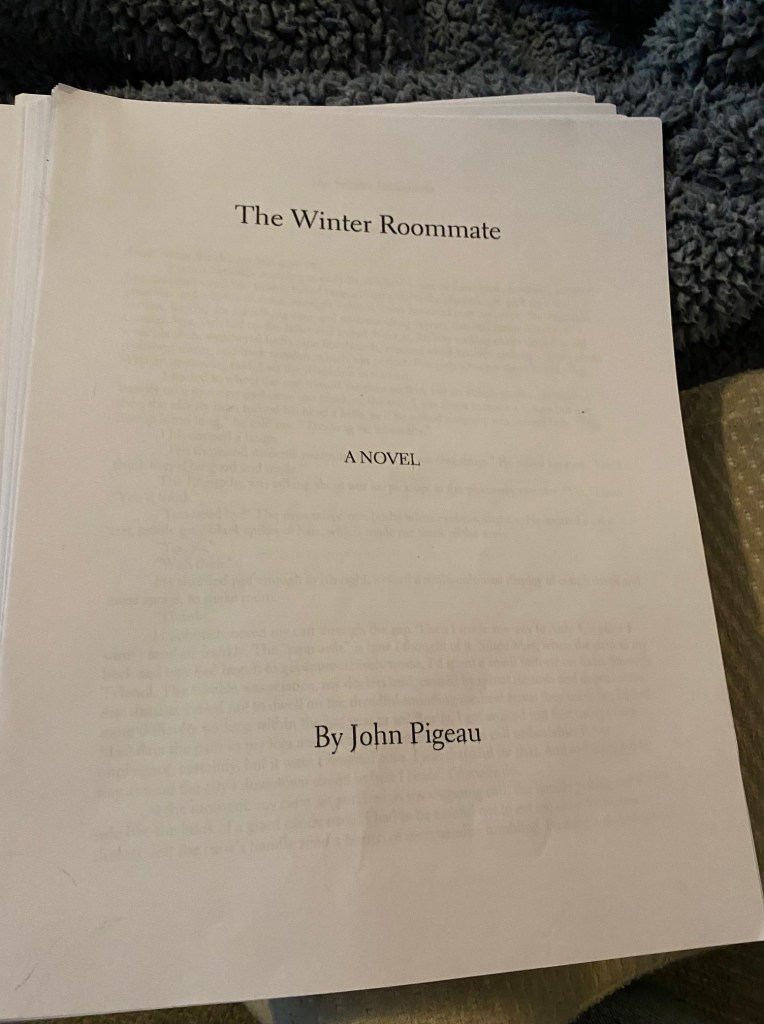

The manuscript of my novel is near me, too. I know where I’ve left my characters. I’m well aware they need tending to. That they have things to say and do. Yes, I sometimes feel guilty, like I’ve neglected them, if I can’t manage to write a new sentence or two in a day, or revise a few lines, or polish up some dialogue; if I haven’t, in any way, moved it forward. That uneasy feeling I get when I leave a bookshop empty-handed — that’s similar to how I feel when I haven’t touched my manuscript at all and it’s the end of the day, and my body and mind are tapped out.

But, like all feelings, that uneasiness passes.

I mean, I’m not out vandalizing cars, right? I’m not at the pub drinking myself silly, either. And I’m not — I don’t know — playing Minecraft for hours on end.

Reading good books actually keeps me focused. I’m mindful of the way a writer styles their sentences. I’m learning that George Orwell was fairly obsessed with gardening. And that the key to good, clean writing, according to Verlyn Klinkenborg, might just be in making short sentences and knowing what each one says. (I’m also now aware that Verlyn, a name I’d never head before, might be an excellent name for a character, perhaps a revelatory genius!) And in reading Julian Barnes’ latest, Elizabeth Finch, I find myself exhilarated to realize, if I hadn’t already realized this, that there really is no “right way” to tell a story. His work is often unconventional. This novel certainly is, and I find his approach refreshing, enlightening, and entirely exciting (even though I found the middle of the book rather dull) — it’s like your favourite English professor whispering a brilliant tip into your ear, something that feels like a secret, clapping you on the back and saying, “And now you know. Off you go to write your masterpiece!”

“Weeks after the baby is born, summer turns to fall.”

That’s the first sentence of Jane Zambreno’s memoir, The Light Room. How crisp and compelling is that?!

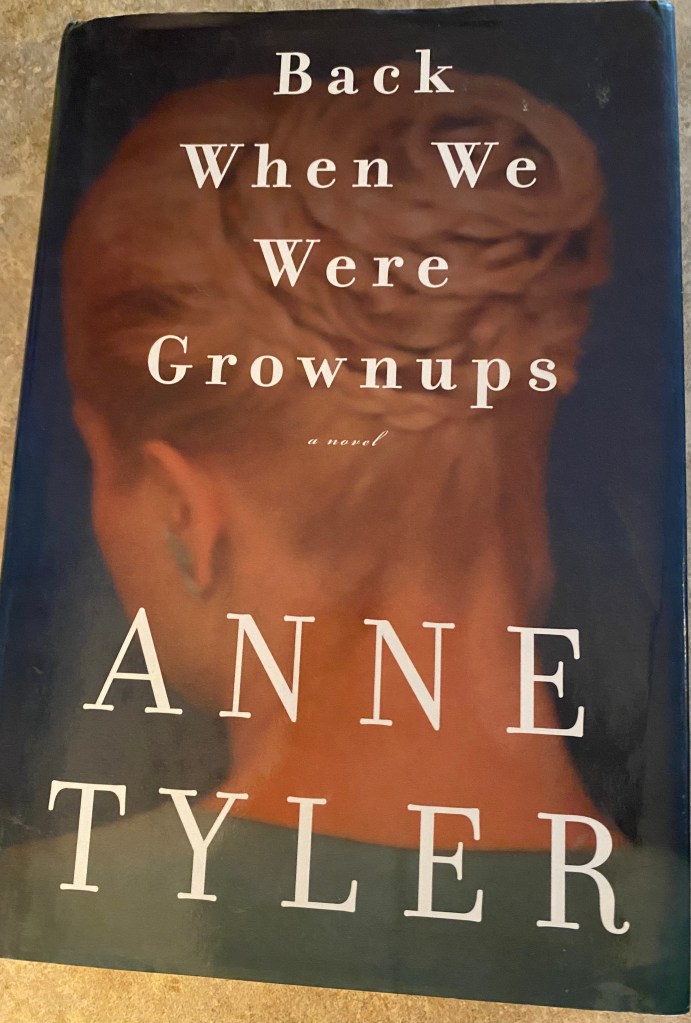

I love first sentences. Sometimes I’ll buy a book because the first sentence strikes me as brilliant. (In fairness, I’ve returned a few of those, or repurposed them, but not many.) Anne Tyler’s first sentences are warm, charming, graceful, funny, poised, sometimes strikingly bold but never snooty, and I’ve fallen in love with every one of them. Here’s the opening sentence from Back When We Were Grownups: “Once upon a time, there was a woman who discovered she had turned into the wrong person.” How audacious! How plucky! And she pulls it off beautifully, which is to say, Back When We Were Grownups is a superb, deeply moving work of fiction — and it just happens to have one helluva catchy first sentence.

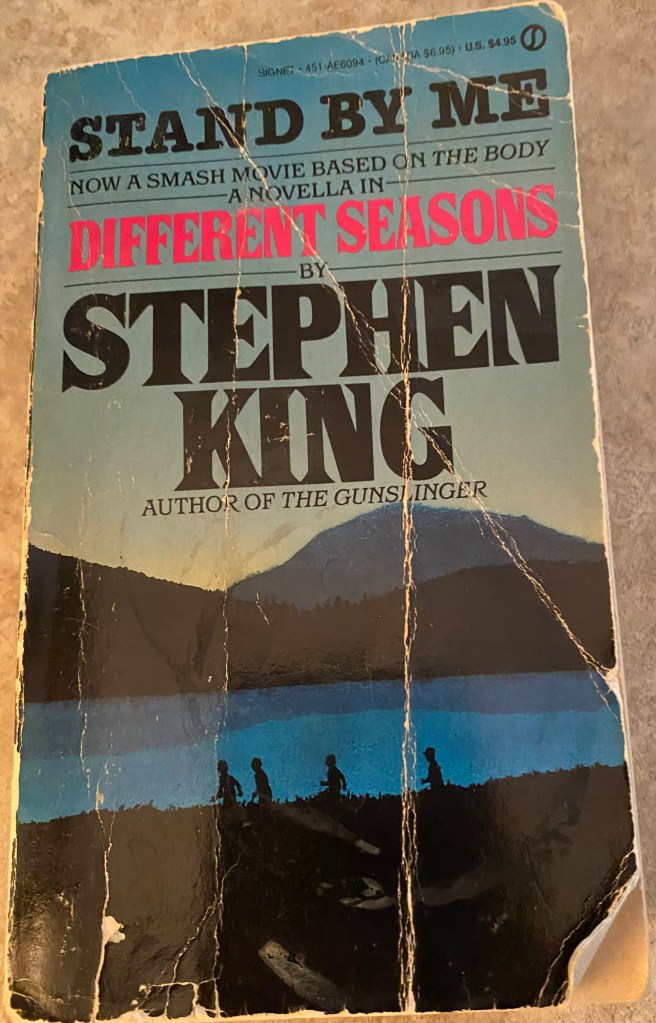

I still remember the first sentence of Stephen King’s novella “The Body,” which was later made into the film Stand By Me (the dialogue almost word-for-word from King’s story, the film’s narrative extremely faithful to the book); it’s this: “The most important things are the hardest things to say.” I first read that book when I was a teenager and worked as an usher at a movie theatre; Stand By Me was playing when I trained, and it played for months and months, and I must have seen it thirty or more times. My paperback copy of Different Seasons is gorgeously scruffy and dog-eared. I think I bought it at Cole’s Bookstore in the mall near the theatre. Anyway, I didn’t need to open the book again to remember that first line. I’ll never forget it.

Reading is never a bad thing. Even when you’re hip-deep in heavily-inked-up manuscript pages, it’s still okay to learn. To allow yourself that gift. I believe it’s a vital part of the writing process. It’s like standing up to stretch after you’ve been at your desk awhile, stepping outside and walking barefoot in fresh-cut grass, feeling the sunshine warming your face, closing your eyes and listening to the leaves shiver in the breeze and the kids next door shouting, “You’re it! You’re it!” And if the air smells like cotton candy, you’d better write that down.

Just maybe a little later.

Leave a comment